Breathwork Holotropic

Childhood trauma & the benefits of breathwork in releasing it

Among the paradoxes we wrestle with is the tension between human resilience and fragility.

Humans have been described as all-terrain vehicles with supercomputers inside that can go anywhere. We’ve survived world wars, major pandemics and outlived dinosaurs.

On the other hand, we are extremely frail. We can only survive a small bandwidth of temperatures. If we lose over a fifth of our body fluid we shut down and die. Think about how susceptible the human eye is.

Scars are often permanent on our skin while our soft tissue makes us vulnerable and deep wounds can result in fatality. After arching our spines to walk on two legs the pressure on our lower vertebrae results in as much as 80% of adults experiencing lower back pain.

One wag said that our bodies are constructed with the biological equivalent of duct tape and lumber scraps. Perhaps we were made this way to remind us that we are spiritual beings having a human experience.

Youth inculcates the belief that we are immortal and bulletproof. But as we get older we get more circumspect.

Moving from the physical shell to contemplate our emotional and psychological states we often adopt a stoic kind of thinking that belies what is really going on internally. In this regard, it takes more conscious effort to realise that we aren’t as unaffected by life events as we tell ourselves.

Breathwork originated from the understanding that we store a great deal of trauma and pain within our bodies.

Transpersonal psychology would argue that we inherit a great deal of baggage from our family lineage.

The psychologist Thomas Armstrong speaks about the impact of prebirth on our psyches:

On a physical level, you engaged in an intricate biological dance with your mother through the Tree of Life /placenta, which acted as a kind of referee or choreographer to keep the two of you in a biochemical balance.

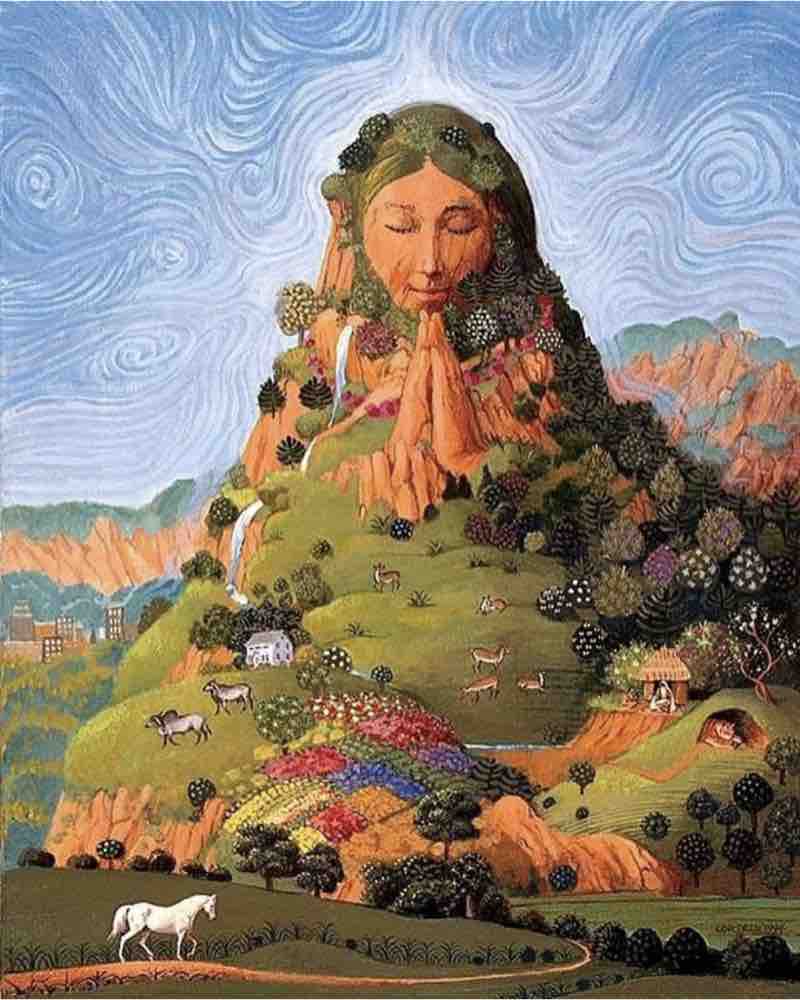

Mother and Child

Though your mother's blood system was separate from yours, she still passed many hormones and chemical signals through the placenta to nourish you. And you also had a part to play as you interacted with these signals through your own chemical responses to keep your mother’s immune system from rejecting you.

Being physically a part of your mother, you were involved in every action of her life. You were there when she had sex, got angry, cried, fought with your father, laughed, vomited, listened to music, and at every other moment besides. And she passed on her subjective moods not just through the physical experiences of jostling, bumping, singing, or rocking you, but through her hormonal responses to the positive or negative emotions in her own life. These hormones essentially set the thermostat on your "emotional climate control" and created intrauterine versions of sunny days and tropical breezes, or thunderstorms and hurricanes.

Scientific studies show that mothers who would have liked to abort the fetus but were prevented from doing so by legal restrictions have children with higher levels of delinquency, emotional disturbance, and physical illness than mothers who actively want their kids.

Mothers who are depressed during their pregnancies give birth to infants who are hard to console when upset, and mothers who are anxious have more cranky and colicky babies. According to one study, a woman trapped in a stormy marriage has a 236% greater chance of bearing a psychologically or physically damaged child than a woman in a safe and supportive relationship.

Curiously, the search phrase "bad mother" is entered over 18 000 times a month in Australia, while "good mother" is only searched for 70 times. This is not to suggest that most people feel their mums weren't loving and caring but perhaps it suggests that many mothers feel they're not living up to the myth of being a perfect parent.

How many of us can say that we experienced an ideal prebirth like the following description?

The Good Mother

A Best-Case Scenario: The Good Womb

Like aboriginal mothers in Australia, your mother began bonding with you even before conception by having dreams about you and drawing images of those dreams. Once you were conceived, like Mbuti mothers in the Congo, she took you to a special place in nature, sung soothing lullabies to express her joy, talked with you about the world that you were about to enter, and gave assurances that life on earth was safe and full of blessings.

She ate a nutritious diet and avoided drugs, alcohol & cigarettes. She also stayed away from any foods that might have had an adverse effect and received regular checkups to monitor the course of her pregnancy.

She enjoyed a loving relationship with your father, who was almost as involved in the pregnancy as she was, rubbing her belly, singing to you, and engaging in lots of hugging and lovemaking.

She meditated and prayed, read stimulating literature, and engaged in her own highly creative life and professional study. She lived with you in a peaceful rural town that included both sides of your extended family, which provided a nurturing support system for the both of you.

Now consider the opposite scenario.

The Negative Mother

A Worst-Case Scenario: The Bad Womb

Your mother was what some prenatal psychologists call a "catastrophic mother." She was a teenager who had dropped out of school when she had you. She didn't expect to have you and she didn’t want you when she realised you were there. She tried aborting you with different folk remedies and flooded you with "rejection" hormones.

She smoked, overused alcohol and took recreational drugs. She didn't eat regular meals but snacked erratically on fast food and candy. She was suffering from several different diseases when she carried you, including tuberculosis, gonorrhoea and chlamydia.

She had a partner, not committed to the relationship, who physically beat her (you felt the punches), periodically left her (you felt the abandonment hormones) and screamed a lot (you felt the stress hormones). While she carried you, her own mother had a nervous breakdown, a war broke out in her native country, and her brother committed suicide.

While these scenarios represent two ends of a spectrum, most of us find ourselves somewhere in the middle.

Philosopher Alain de Botton said that “Everyone around us may have been trying to do their best and yet we end up now, as adults, nursing certain major hurts which ensure that we are so much less than we might be.”

The imbalances go in endless directions. We are too timid or too assertive; too rigid or too accommodating; too focused on material success or excessively lackadaisical. We are obsessively eager around sex or painfully wary and nervous in the face of our own erotic impulses. We are dreamily naive or sourly down to earth. We recoil from risk or embrace it recklessly. We emerge into adult life determined never to rely on anyone or are desperate for another to complete us. We are overly intellectual or unduly resistant to ideas. The encyclopaedia of emotional imbalances is a volume without end.

Because we are largely oblivious to our emotional pasts and heritage we too easily take our temperament as our destiny.

Hypnotherapy and other techniques endeavour to help people readdress beliefs and patterns of behaviours that have their origins in our subconscious. Breathwork is another tool that helps to bypass the conscious mind and allow our bodies to release inherited beliefs and ideas that don’t serve us.

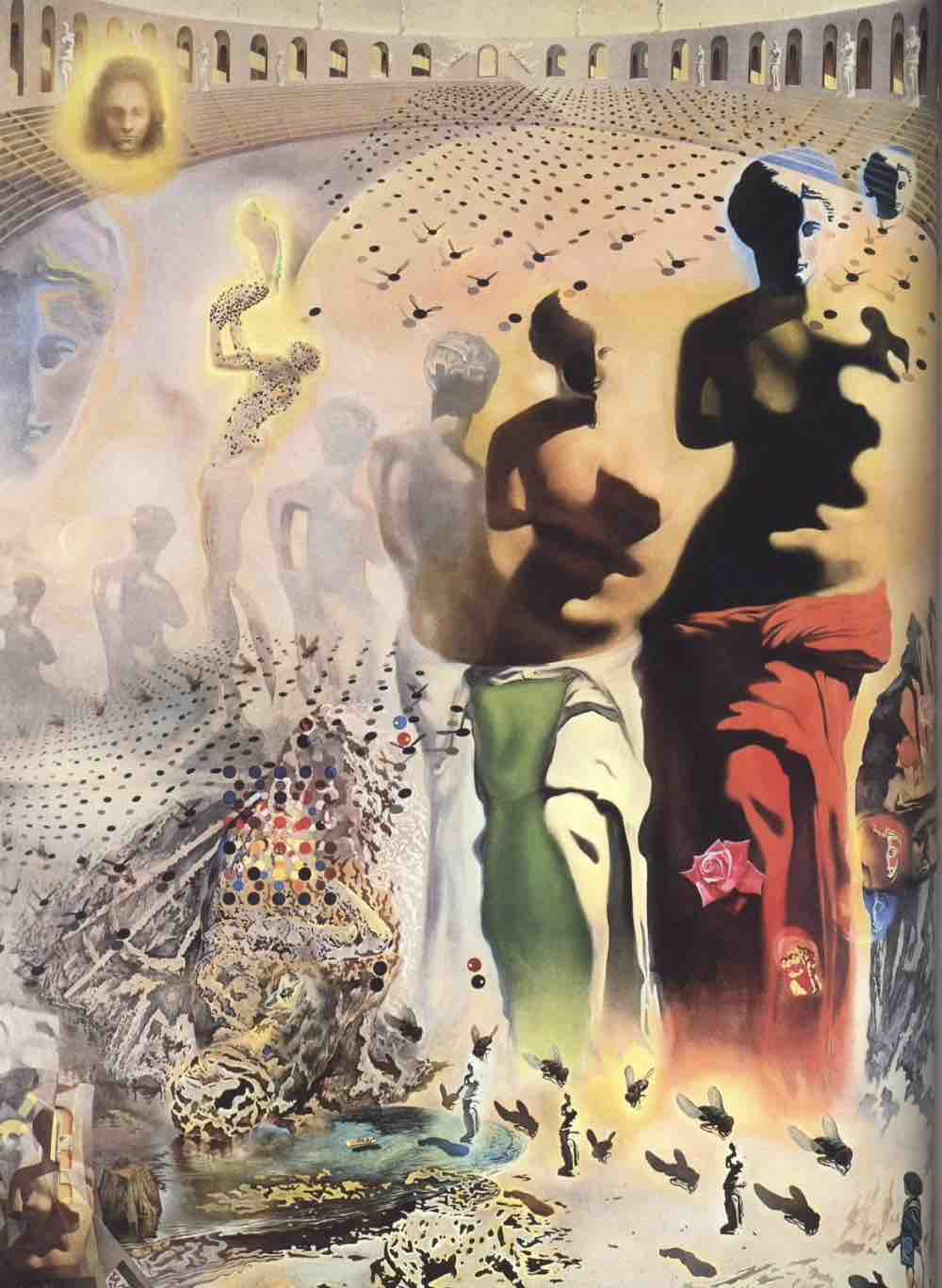

Salvador Dalí's Hallucinogenic Toreador

Three years before the surrealist painter Salvador Dali was born, his parents had lost a son to meningitis. According to Dali, they never recovered from it and the anguish over the loss felt by his mother while pregnant with Salvador was transferred directly to the unborn artist-to-be. He claimed to remember his own intrauterine existence and wrote that it was hellish:

”My fetus swam in an infernal placenta I have only to close my eyes, pressing on them with my two fists, to see again the colours of that intrauterine purgatory, the tints of Luciferian fire, red, orange, blue-glinting yellow; a goo of sperm and phosphorescent eggwhite in which I am suspended like an angel fallen from grace."

Alain de Botton pointed out that “childhood opens us up to emotional damage in part because, unlike all other living things, Homo sapiens are fated to endure an inordinately long and structurally claustrophobic pupillage. A foal is standing up thirty minutes after it is born. A human will, by the age of 18, have spent around 25 000 hours in the company of its parents.”

The modern era has done wonders for helping us cut the apron strings to our parents and allow us to live in whatever environment and culture we find more conducive to our flourishing.

Ultimately though, the great length of time we’re under our parent's influence combined with the vulnerability of childhood means that a lasting impact occurs.

Counselling and psychotherapy are wonderful tools to help us understand and reconcile with our mother imprints. But nothing is more fundamental to life than breath and in my experience, no modality brings about deeper and lasting change than that of breath work. As one of my clients attested:

"After almost 30 years of trying different therapies I have at last found Ginny's form of breathwork to be an absolute breakthrough as it bypasses the brain and goes straight to the body which holds all the trauma. What a revelation! Letting your body express what is held inside is incredibly liberating. Breath work did what years of talking therapy couldn’t."

Holotropic breathwork was pioneered by the psychologists Stanislav and Christina Grof in the 70s. They were interested in more experiential approaches to psychotherapy and found that the technique often brought about altered states in the people they worked with. You can read more about the history of breathwork on the following link...